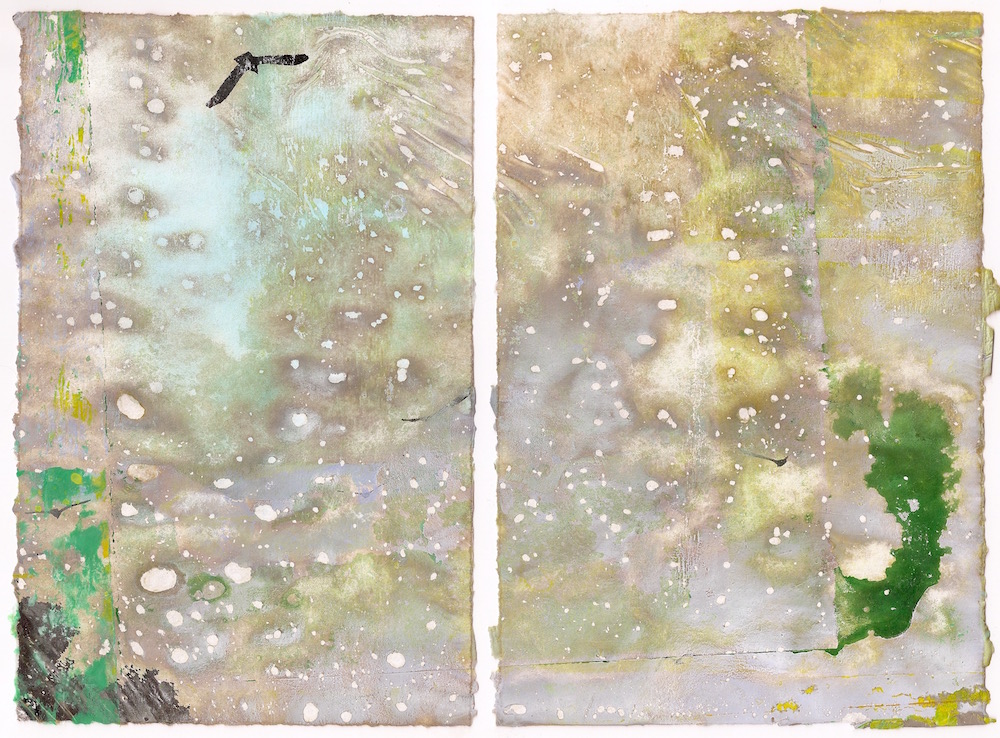

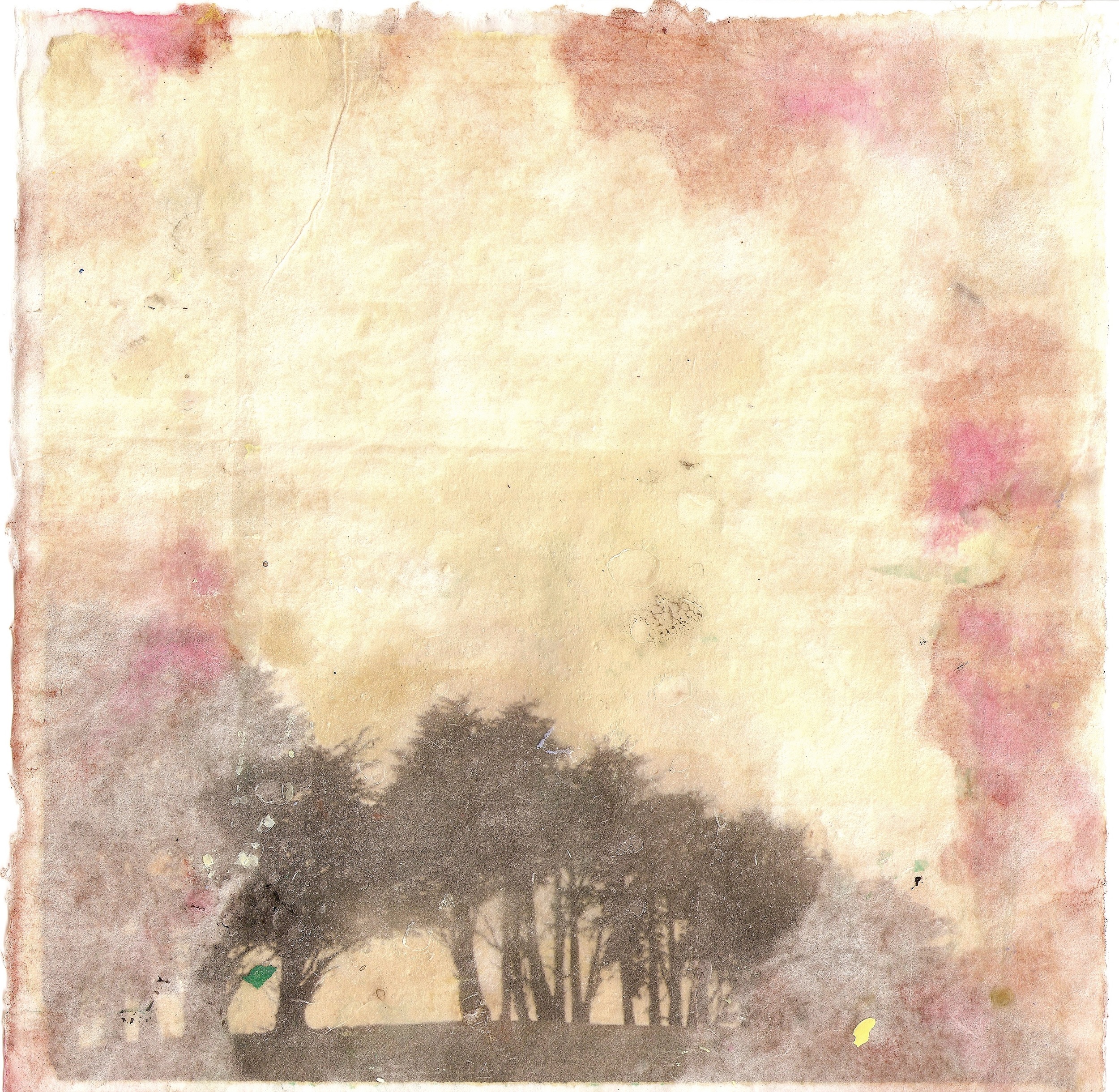

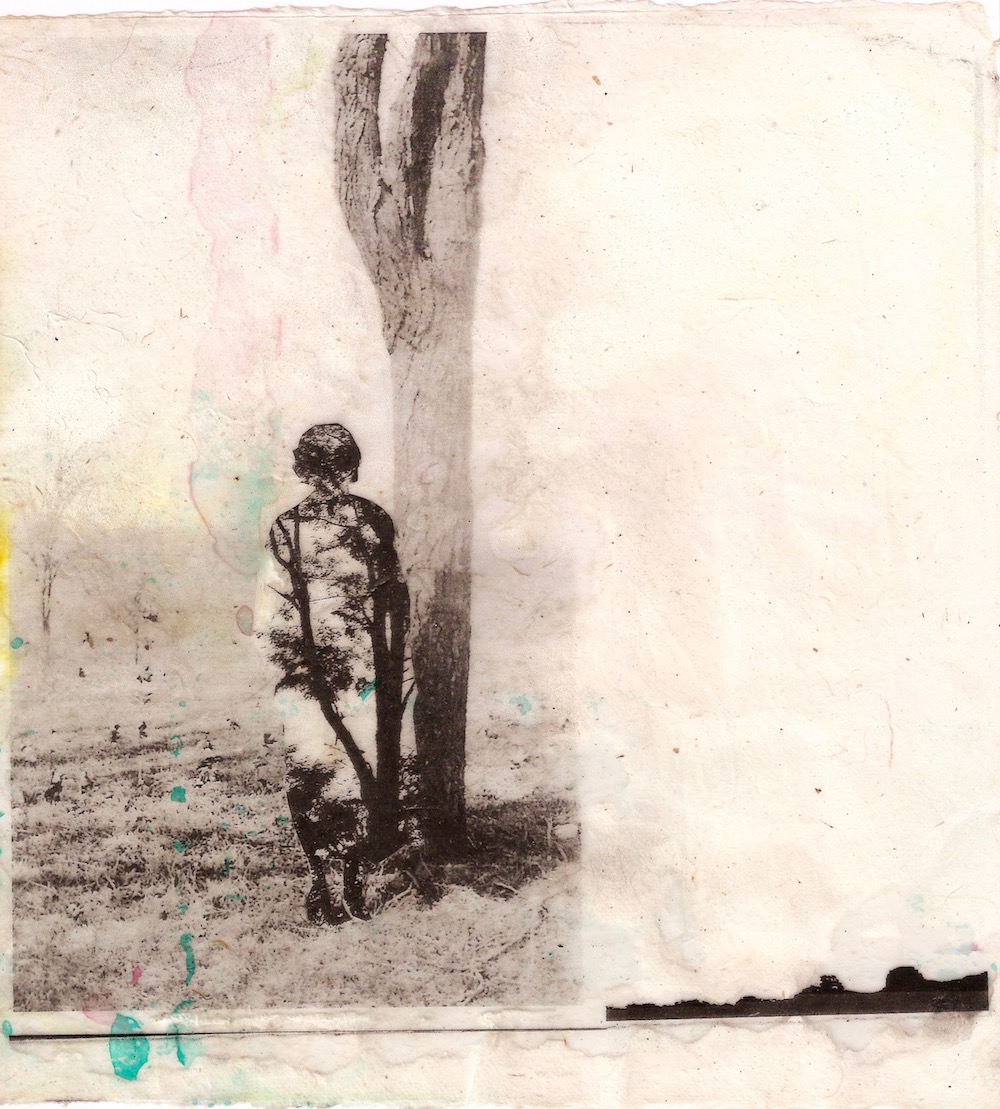

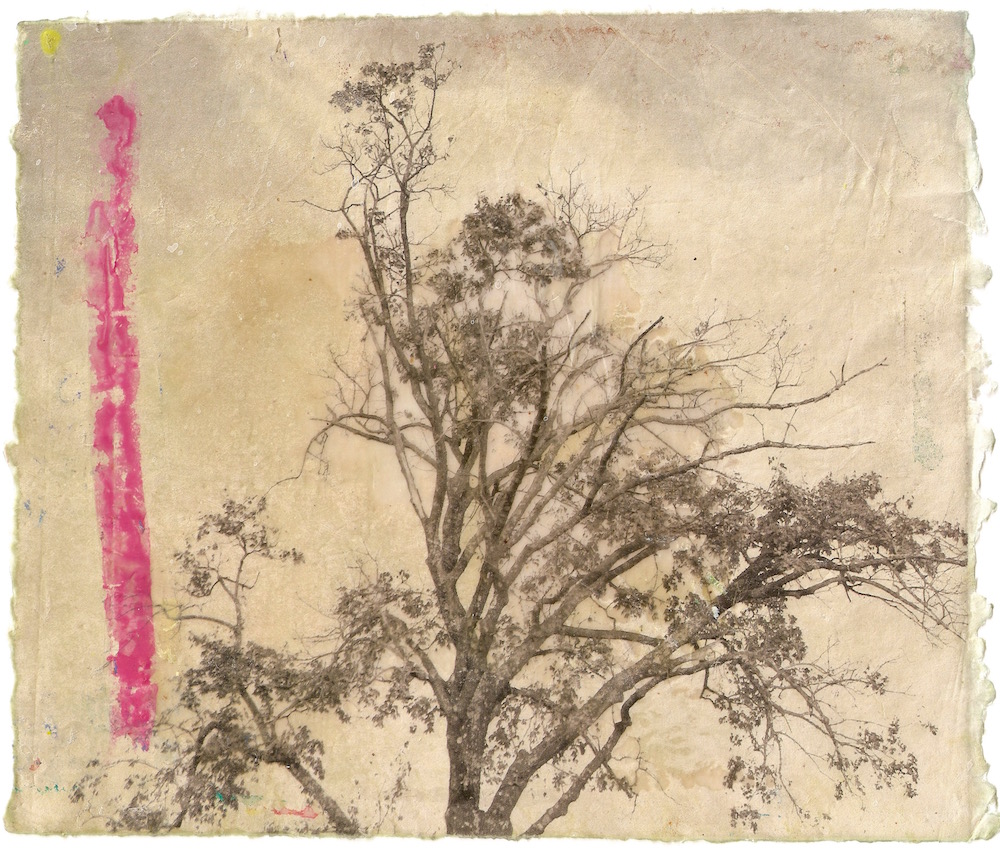

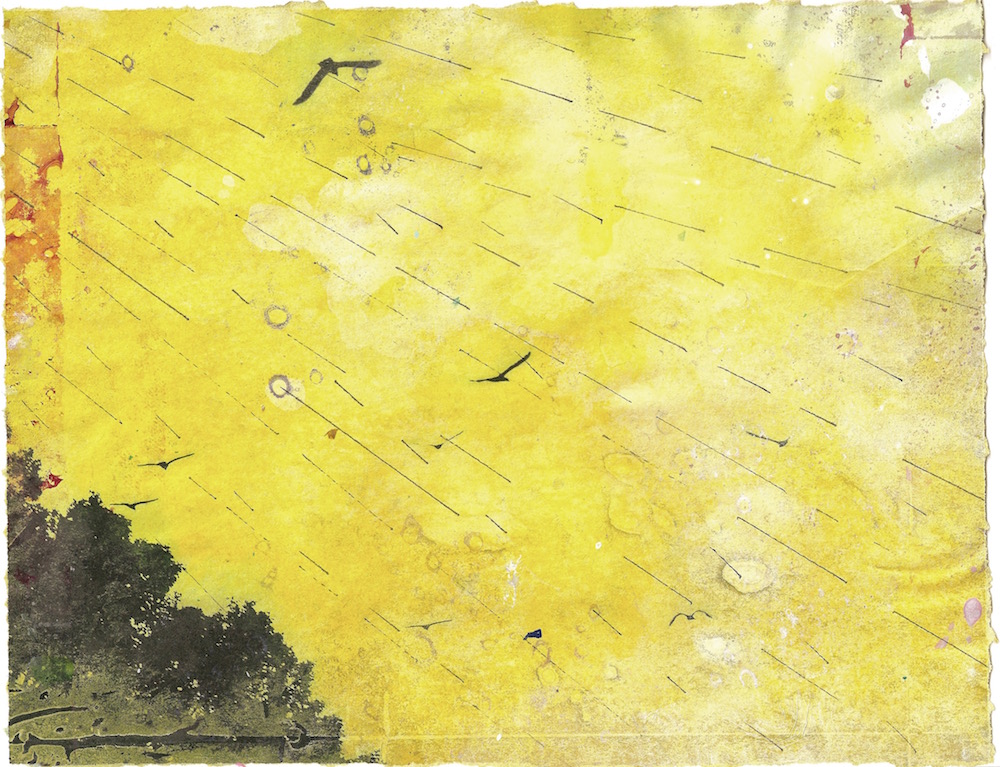

All work: gouache and ink on paper (2011-2012)

ARTIST STATEMENT

1 What can I say? There’s nothing to say about trees. That’s the point. More significantly, it seems there’s nothing to see about trees either. Not any more. We have seen trees. But as it happens, “the hardest thing of all to see is what is really there” (J. A. Baker).

2 Unable to find a major publisher for A River Runs Through It, Norman Maclean was told by way of explanation, "These stories have trees in them” — as if trees could ever lose our interest.

3 But nothing makes me feel my time like the corkscrew willow in the backyard with its short life. Now the shoot from the stump is nearly as tall as the sapling we planted. Nor does anything make me feel my time more than the weeping cherry beside the willow or the ground beneath its large canopy covered in a tiny forest of weeping cherries that will never grow. And nothing can make me know my time the way two barren hillsides do, now forested on both slopes.

4 You might say, “Ah, what an age it is / When to speak of trees is almost a crime / For it is a kind of silence about injustice!” (Bertolt Brecht). And you would be right.

5 On the other hand, as I round a familiar bend in the road, I meet the ghost of a beloved sycamore. The profile of its absence stands out like a phantom limb. Anticipating the low crook in its trunk, its gentle tilt back toward the bank, it is not there. I never photographed or painted it, though I meant to. Where could I park my car?

6 The storms have taught us how quickly our horizons can be altered, how the vertical becomes horizontal. The sugar maple and the black locust are also gone.

7 Kandinsky famously claimed, “the inner element of the work is its content.” His non-objective Parisian canvases isolate and distill the graphic elements of form in order to compose an affective symphony for sight. Lauded and condemned for his immaterialism, it’s sometimes forgotten that he thought the principle of art was the principle of the cosmos. The reduction and abstraction of visual phenomena is not a matter of preference for geometry over biology but of attention to the way the visible mark — a line, for example — impacts us interiorly. If we bracket the objectness of the object for a moment, if we stop seeing things as this or that, according to use or convention, we might perceive inwardly — perhaps for the first time — the lilting vertical of the black locust in the open pasture with its loose shock of centric lines. “The world sounds.”